Facts About Rapa Nui (Easter Island)

Location

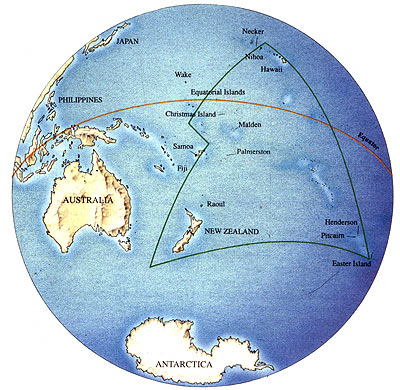

Lying isolated in the East Pacific, in an extreme windward position, Rapa Nui is the easternmost Polynesian island. It is in the Southern Hemisphere at 27° 9’ S latitude, 109° 26’ W longitude. Situated on the Nazca Plate at a volcanic and tectonic “hot spot,” it is 3703 km west of South America and 1819 km east of Pitcairn island. The total land area is 163.6 sq km or 63.2 sq mi.

Map showing the location of Rapa Nui (Easter Island) within the Pacific Ocean and the Polynesian triangle.

Environment

Climate

The island lacks a reef, but there are six known species of coral present, two of which are endemic. Coral was used to fashion eyeballs for the monolithic statues. The island is roughly 160 sq. km in area. The climate is subtropical to temperate, with an average annual temperature of 22 C and average rainfall between 1250 and 1500 mm per year. Winds are nearly constant, with southeast trade winds dominant from October to April. Environmental hazards include tsunami (tidal waves) and drought.

Pacific Breakers on the south coast of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), 1983. Photo: David C. Ochsner, copyright Jo Anne Van Tilburg/EISP.

Coral along the coast of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), 1983. Photo: David C. Ochsner, copyright Jo Anne Van Tilburg/EISP.

Topography

The Rapa Nui landscape is one of gently rolling hills and slopes irregularly punctuated by volcanic cones. Lava plains are frequently densely carpeted with loose rock cover. Maximum elevation is 510 m above sea level. Fresh water is found in two large crater lakes, and seasonal streams flow from Maunga Terevaka vicinity.

Rolling, treeless terrain of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), 1984. Photo: David C. Ochsner, copyright Jo Anne Van Tilburg/EISP.

Geology

Rapa Nui is a Pacific high island, formed by the coalescing flows of three Pliocene to Holocene age volcanoes. Basalts and andesitic rocks are characteristic, and soils are predominately loams and clays. In part because of previous deforestation, soil erosion is a problem today. The island’s most culturally significant geological resource is Rano Raraku, a volcanic crater of concentrated ash, or tuff, from which the monolithic statues, or moai, were carved.

Rano Raraku, the volcanic cone of consolidated tuff from which 95% of monolithic statues were carved, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), 2002. Photo by: Jo Anne Van Tilburg/EISP.

Totora reeds circling the crater lake on the interior of Rano Raraku, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), 1989. Photo: David C. Ochsner, copyright Jo Anne Van Tilburg/EISP.

Flora

Rapa Nui was largely forested before humans settled it. About 16 species of trees or woody shrubs existed, and at least one large palm (similar to Jubea chilensis). An alternative hypothesis is that the island was grass-covered with palm trees and shrubs concentrated in lowland areas. In either case, the island was largely deforested by the coming of Europeans in 1722. Scripus californicus, commonly called the totora reed, colonized the island by natural means some 30,000 years ago. It is widely agreed that deforestation attained a level of irreversibility, and had significant ecological repercussions. There is, however, considerable scholarly debate about the proportionate interaction of human and natural forces—such as drought, for example—in bringing about deforestation.

Fauna

There were no indigenous large or small mammals on Rapa Nui before human settlement. There were, however, insects and at least one species of lizard. Twenty-five seabird species, from sub-Arctic to tropical, and six types of land birds are archaeologically known. Of 111-140 species of fish inhabiting the marginal marine ecosystem, only 54 of them are near-shore or offshore species. Human impact on birds was significant, and caused the extinction of about half a dozen land birds and several dozen seabirds. Central South Pacific planktons were a major food source for migrating tuna and other large fish important to the Rapa Nui economy.

About Prehistoric Rapa Nui Society

Social Organization

The basic social units on Rapa Nui were the family (paenga), the lineage (ivi) and the clan (mata). A cluster of defined features, including the hearth (umu pae), marks households archaeologically. Households were linked to the extended clan through a complex web of economic and social obligations that prompted and sustained cooperative exchange of goods, wives, and labor. This method of organization is called the conical clan. The paramount chief (ariki mau) was at the peak of the social pyramid. Public work projects, including the construction of image ahu (temples) and the erection of monolithic statues (moai), were the driving economic forces in food production, storage, display, and redistribution.

An elliptical, high status house foundation (hare paenga) near Tahai, 1983. Photo by: Jo Anne Van Tilburg. © Jo Anne Van Tlburg/EISP.

Political Organization

The Rapa Nui chiefdom was organized in the same basic manner as all other Polynesian chiefdoms. The paramount chief (ariki mau) was drawn from the Honga lineage of the ruling Miru clan, and was descended directly from Hotu Matu’a, the legendary founding ancestor of the entire Rapa Nui family. Associated with the site of Anakena, he was considered to be the repository of divine power called mana. Subordinate chiefs (ariki paka) in the same direct line were arrayed below, and non-direct line chiefs (honui) followed. Each had power (mana) and sanctity (tapu) corresponding to their hereditary rank and status. All non-chiefs and other members of society also held ranked positions, but status could be acquired through demonstrated excellence or leadership.

Rapa Nui fishhooks (mangaia), including one of basalt (top) and one of human bone. Photo by: David C. Ochnser. Copyright Jo Anne Van Tlburg/EISP. Courtesy Museo Antropologico Padre Sebastian Englert (MAPSE), Rapa Nui (Easter Island).

Division of Labor

Culturally dictated gender specialization made many work tasks (such as fishing) forbidden, or tapu to women. Tools were often sanctified. Human bone, for example, was sometimes used for fishhooks, and may have been believed to incorporate the mana of deceased expert (maori) fisherman. Expert carvers of statues used stone tools (toki). All professions were organized, and those who belonged to esteemed societies or guilds were treated as privileged. Skills were passed down from one generation to the next in an organized manner.

Access to Resources

Resource management, including access to prestige goods and restricted resources, was guided by the hierarchical power structure. Some resources were controlled through the traditional Polynesian system of tapu restrictions. The paramount chief and expert fishermen, for example, controlled access to deep-water fish resources. Stone of at least three types was restricted to specific uses. Rano Raraku, the volcanic quarry from which 95% of the statues was hewn, is surrounded at its base by a ring of elliptical house foundations (hare paenga) widely interpreted as the remains of high-status dwellings. This suggests control of the stone by a ritual or technological elite.

Conflict

Rapa Nui spearpoints (mata'a), 1983. Photo courtesy Museo Antropological Padre Sebastian Englert (MAPSE), Rapa Nui, (Easter Island).

Archaeologists, linguists and osteologists have established that competition and conflict are fundamental structural characteristics of ancient Polynesian chiefdoms. On Rapa Nui, social tensions were deep and conflict emerged at different times at various levels of society. It became more pervasive when the upward trajectory of population growth and public works—including the making of monolithic statues—intersected with the downward spiral caused by deforestation and resource depletion. Obsidian spear points (mata’a) appear in large numbers in late archaeological contexts. Two large regional polities existed: the lower ranking, eastern group of clans was known as Hotu Iti; the higher-ranking, western group was Ko Tu’u. Warriors (toa) were members of a professional guild or class and wore distinguishing feather headdresses. Expert warriors (matatoa), in the opinions of some researchers, eventually usurped all but the most basic rights of the traditional paramount chief.

Rapa Nui Religion, Art, and Aesthetics

The Rapa Nui Universe

Rapa Nui people saw the world as dualistic, and structured the universe symbolically into horizontal and vertical space. Gods were responsible for maintaining permanence. The sky world (light) and the underworld (dark) were separated—but also joined—by the terrestrial realm (kainga). Rapa Nui gods, in the Polynesian tradition, were chiefly ancestors who derived their power (mana) directly from major gods (atua). The clan gods of the Miru, the paramount clan, were the traditional Polynesian male god Tiki and Makemake, said to be the supreme creator god. Lesser spirits and dangerous ghosts (akuaku) roamed individual family lands.

Ancestral Gods

Ancestral gods were the sources of personal protection for the soul and body during life and in afterlife. They guarded lineage territory and personal property from humans and demons, and were responsible for increasing food. They were believed to bring migrating birds and fish to the island, to improve soil fertility and produce new plants, and to increase the human population. The monolithic statues (moai) are universally regarded on Rapa Nui today as representations of chiefly, deified ancestors. They are the “living faces” (aringa ora) of the past.

Moai 89, from the exterior slope of Rano Raraku, 1983. Photo by: David C. Ochnser. © Jo Anne Van Tilburg/EISP.

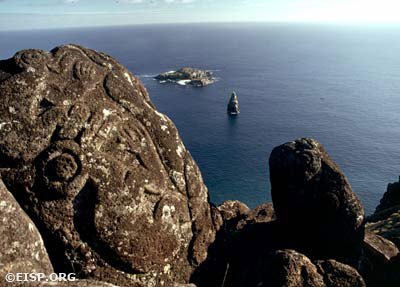

Orongo, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), 1989. Photo by: David C. Ochnser. copyright Jo Anne Van Tilburg/EISP.

Moai 88 and 89, from exterior slope of Rano Raraku, Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Photo by: David C. Ochnser. copyright Jo Anne Van Tilburg/EISP.

Religious Practitioners

The highest-ranking Rapa Nui priests were the powerful ivi atua. They conducted the most complex mortuary ceremonies before the massive, upright moai on image ahu. Ivi atua are linked with stone towers called tupa, where they interpreted signs from the natural world and intoned prophesies related to planting, harvesting, and fishing. A special group of priests created and controlled kohau rongorongo, wood boards or staves with rows of tiny, carved symbols. They employed these symbols in chanting or singing during rituals held at Orongo, a ceremonial village on the rim of a volcano called Rano Kau. There were other, lower ranking male and female spiritual practitioners, including sorcerers, healers, diviners, and prophets.

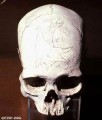

Human cranium with incised design, Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Photo by: David C. Ochnser. copyright Jo Anne Van Tilburg/EISP.

Burial

Rapa Nui mortuary practices included the exposure of the corpse on a raised bier in front of the image ahu. Cremation was conducted at the rear of the ahu. Burial practices changed after about A.D. 1400-1500, and tombs were excavated into ahu that had been converted into semi-pyramidal structures by covering fallen moai with a mantle of rubble. Burials were also placed within the ahu fill, in boat-shaped or wedge-shaped stone structures called ahu poepoe, and in rectangular avanga. Some cave burials are known. A scatter of red scoria stone or broken white coral is usually associated with burials or cremations. Preservation of the human skull was common, especially when the deceased was high-ranking.

Arts

The rich Rapa Nui aesthetic tradition is rooted in Polynesian forms and emphases. Yet it has its own unique, consistent iconographic vocabulary. The human form is most commonly depicted in sculpture, followed by bird and marine forms. Many objects, including some moai, show evidence of having been painted red or white. A diagnostic characteristic of Rapa Nui sculpture, including rock art, is a “morphosis” or transformational quality (a being turning into another being). In addition to sculpture, tattoo and some rock art were well advanced. A very few superb objects made of feathers, barkcloth (tapa), or shell have been preserved in museum collections. Contemporary arts on Rapa Nui are vibrantly alive.

Want to know more?

Erosion on the north coast of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), 1989. Photo: David C. Ochsner, copyright Jo Anne Van Tilburg/EISP.

Baker, P.E. 1967. “Preliminary account of recent geological investigations on Easter Island.” Geology Magazine 104:2.

Hunter-Anderson, R. 1989. “Human vs. climatic impacts at Rapa Nui: Did the people really cut down all those trees?” In Easter Island in Pacific Context: South Seas Symposium, ed. C.M. Stevenson et al. Los Osos, CA: Easter Island Foundation Occasional Paper 4, 85-99.

Martinsson-Wallen, H. 1994. Ahu—The ceremonial stone structures of Easter Island. Uppsala: Societas Archaeological Upsaliensis Aun 19. Orliac, C. 2000. “Des arbres à l’île de Pâques entre le 14 ème siècle de notre ère.” Paris: L’Archèologie “Errance.”

Steadman, D.W., P. Vargas and C. Cristino 1994. “Stratigraphy, chronology, and cultural context of an early faunal assemblage from Easter Island.” Asian Perspectives 33: 79-96.

Van Tilburg, J. 2001. “Easter Island.” In P.N. Pergrine and M. Ember (eds.), Encyclopedia of Prehistory. Human Relations Area Files at Yale University. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

English

English  Español

Español