Hoa Hakananai’a Laser Scan Project

September 2007

Background, Rationale and Goals

To date, Van Tilburg and the Easter Island Statue Project (EISP) have inventoried 887 monolithic statues (moai) and compiled a metric database buttressed by 24,000 original and archived images. Some 35% of the known statues are located on or in direct relation to ceremonial sites called image ahu (Martinsson – Wallin 1994: Appendix 1 gives 164 image ahu; Van Tilburg 1986; Van Tilburg and Vargas C. 1998).

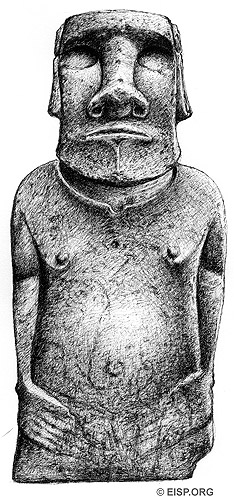

Rano Raraku, a volcanic crater on the island’s eastern plain, was the source of the sideromelane (basaltic) tuff from which 95% of the statues were carved. This source is irrefutable as there are 397 in situ statues, of which 141 in various stages of completion have recently been mapped by EISP in the interior quarries (Van Tilburg 2005; www.eisp.org). Much rarer statue lithologies are basalt (hawaiite lavas) from three named regions; trachyte and ‘red basaltic scoria’ or ‘red scoriaceous lava’ (also used as pukao or ‘topknots’ that were placed on the heads of about 75-100 statues).

There are only 20 statues (portable and non-portable) now in the EISP database which were carved of basalt. Of these, 7 are in museum collections. The British Museum holds two basalt statues, both of which are of central and very great significance to furthering our understanding of Rapa Nui history. One of them (1869.10-5.1) is re-carved on its dorsal side with bas-relief and incised petroglyphs of great iconographic significance. This re-carving is unique in its style, detail, and expertise and quality of execution. Four other statues, including 1869.10-6.1 (Moai Hava), have incised petroglyphs of lesser distinction but within clearly defined, limited typological categories. Another 30 statues still in situ on the island have applied decorations of similar styles.

The site from which 1869.10-5.1 was collected by HMS Topaze in 1868 is Orongo, and the archaeological and late ethnographic context for the statue and the site has been reconstructed by Van Tilburg (1994, 2005) in papers published by British Museum Press. Geographically within the Miru political district at Rano Kau (where the latest intrusions of lava are 240,000, 340,000 and 180,000 BP), Orongo was the focal point of Miru-dominated, island-wide religious practices from c. AD1400 (the “birdman cult”). The petroglyphs superimposed upon the dorsal side of Hoa Hakananai’a are directly comparable to a complex of over 500 similar petroglyphs carved on boulders at Orongo, elsewhere on the island and on portable objects in various museum collections. Hoa Hakananai’a is the best documented, most distinctive iconographic link between two distinct artistic traditions (the statues and petroglyphs, or rock art) and two discrete but interwoven sets of ritual practices: the earlier statue dominated religion and that of Orongo.

To date, Van Tilburg and C. Arévalo Pakarati have examined, photographed and drawn to scale the carvings on Hoa Hakananai’a. We have recorded, measured and mapped relevant rock art imagery in situ on the island. We hypothesize that, when the proposed laser scan is achieved, the details of dorsal design carvings (perhaps including the types of tools used) which we have only partially or incompletely discerned or recorded will emerge. We intend to compare the laser scanned results with field documents and strengthen the unequivocal iconographic linkage between Hoa Hanakanai’a and Orongo. A geographical and iconographic baseline for the political district of Orongo will be further substantiated.

Methods of Data Collection and Analysis

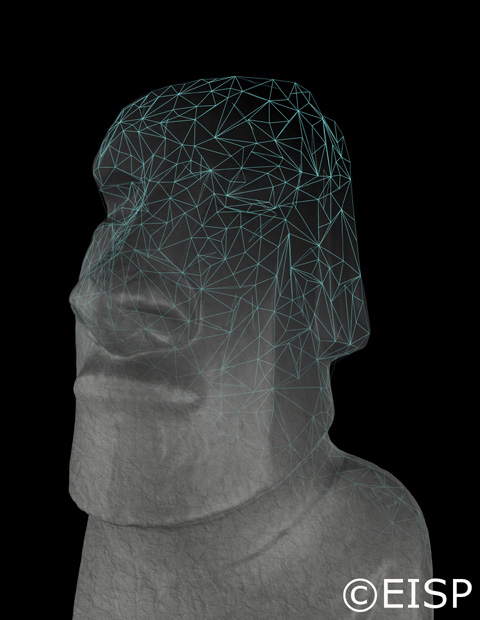

On 6 August 2006 Van Tilburg and a crew of three undertook the first ever laser scanning of any object in any collection in the history of the British Museum. This methodology was non-invasive and non-intrusive, and at no time was there any contact with the surface of the statue.

We used portable, hand-held equipment to survey and scan the outside configuration on four sides and the top of Hoa Hakananai’a. The procedure was planned and organized by Mr. Gary Farrow of Z + F UK with Van Tilburg, and conducted by a crew of 2, a scanning engineer and a surveyor, under the supervision of Van Tilburg and in the presence of Natalie Smith, British Museum staff. Previous experience in directly comparable projects include Z + F UK projects for English Heritage scanning Tynemouth Priory, Chester Amphitheatre, Ironbridge and Studley Royal. The resulting digital scan was prepared by Andrew Simmons of Z + F UK and is being imaged by Debra Isaac of EISP to produce a three-dimensional image of the statue and its dorsal carvings.

The equipment used was a Z+F Imager 5003 developed and widely used to capture 3D Dimensional data in planning of factories, industrial plants, architecture, protection of historic monuments, landscape and virtual reality. An Imager 5003 has 360 x 312 degrees field of view. Each scan took approximately 6 mins to capture 11 million 3D data points, giving accuracy sub 3mm @ 10M range. The scanner was mounted on a tripod and powered by one small portable battery. Data storage was on a field laptop.

Scanning required about 16 removable targets A5 size to be placed around the gallery in which the statue is displayed. The targets had no physical contact with Hoa Hakananai’a. Targets were immediately removed once scanning was completed.

The estimated completion time was approx 4 hours after museum visitor hours, and no disruption of public access to the gallery was caused. A temporary scaffold and platform was required to elevate the scanner to allow scanning of the top of the statue.

Value of this Scanning Project

The on-going research conducted by EISP is a complex effort that is designed to study the monolithic statues fully within their archaeological and geographical contexts. Because of the broad and deep range of data it encompasses, this project has the ability to address a wide variety of research questions. Further, it is the single most valuable site and statue conservation tool currently available on Easter Island. The addition of the data gathered during this scanning project, as well as that being gathered at other museums, will provide one-fourth of the total iconographic data available world-wide on the basalt statues of Easter Island. It will further the understanding of Easter Island museum object history; it will strengthen iconographic baseline and comparative data for the island as a whole, and it will clarify the use of ethnographic information to explain archaeological phenomena.

Acknowledgements

Lissant Bolton, The British Museum

Natasha Smith, The British Museum

Gary Farrow, Z + F UK

Andrew Simmons, Z + F UK

Johannes Van Tilburg

Debra Isaac

English

English  Español

Español