Easter Island Statue Project History: 1989

Goals and Methods

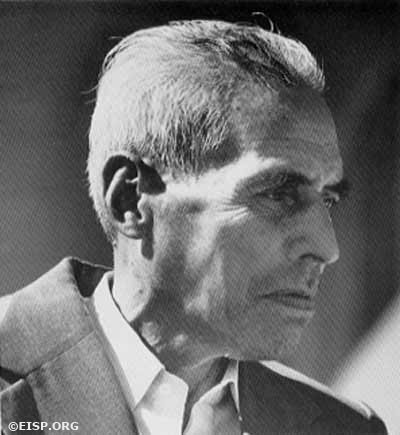

David C. Ochsner, Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Curtiss H. Johnson, Luisa Fati, Cristián Arèvalo Pakarati (and the National Geographic Society flag), Vai Mata, Rapa Nui. Photo by David C. Ochsner, © JVT/EISP.

The specific archaeological purpose of the Easter Island Statue Project, since its inception, is to inventory the statues throughout the island. The method used to accomplish this goal is that of archaeological survey. During the inventory process, the statues are described through the documentation of metric attributes, but also through statistical evaluation of volume, cross sectional area, and center of gravity. We employ a standardized recording format and use special, large-scale calipers or measuring devices. The model for this type of work is found in a wide range of artifact studies, including lithics or pottery analysis and osteometrics.

This post-dissertation research was funded by the National Geographical Society. It was meant to extend the statue site aspect of the generalized archaeological survey to the north and west coasts, Anakena to Vai Mata (quadrangles 26, 32, 33, 34, 35), and to the Poike peninsula (independently being surveyed at about the same time by the University of Chile). We hoped to correct inconsistencies discovered in one or more of eight key measurements on forty-eight statues. If time permitted, we would document the statues on the restored site of Ahu Akivi for comparison and validation studies.

David C. Ochsner, Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Curtiss Johnson (and National Geographic Society flag), Rano Raraku, Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Photo by David C. Ochsner, © JVT/EISP.

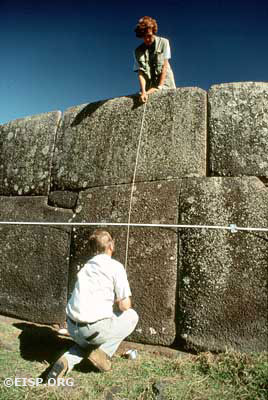

In terms of furthering our interest in ahu design and construction, we intended to collect measurements of ahu platform lengths to establish the range of structural size and scale related to statue size and number, and to produce maps and plans of ahu construction variation. Based on our previous fieldwork and discoveries related to the use of red scoria, we wanted to document the occurrence or non-occurrence of red scoria as cornerstones and architectural enhancement. Finally, we had formulated questions about siting and previous construction on ahu sites, and planned to produce elevations showing the variation in seaward and landward wall construction.

In the Field

Graphic artist Cristián Arèvalo Pakarati joined our crew. His paternal great-grandfather was catechist Nicolás Pakarati Urepotahi, and his maternal great-grandfather was Juan Tepano. Tepano, of course, was Katherine Routledge’s field assistant during her work with the Mana Expedition to Easter Island, 1913-15. They worked together to map large portions of the island, and to re-establish the ancient lineage and family boundaries that, while not obliterated, had been blurred by colonial sheep ranching and the repeated blows of European contact. The success of the Mana Expedition, Katherine wrote in The Mystery of Easter Island, “was due to the intelligence of one individual who was known as Juan Tepano.” Over the years we have worked together closely, and Cristián has progressed from artist to field assistant to co-director of the EISP.

Our crew camped at Anakena, surveying the north coast on foot while Rapa Nui helpers covered it on horseback. When a statue was located we first recorded its exact location, position and the orientation of its head. Following that we noted type of material; body and head shapes, and the presence or absence of five distinguishing characteristics. In addition, a series of conservation observations were made, including the color and condition of the surface stone, water retention, and vandalism.

David C. Ochsner, EISP photographer, took four black and white photographs of each statue we found. The large-scale calipers required for recording the largest statues in the quarry and on the transport roads (more than 10 m long) were not needed in 1989. Architect Curtiss Johnson drew plans and elevations of numerous ahu.

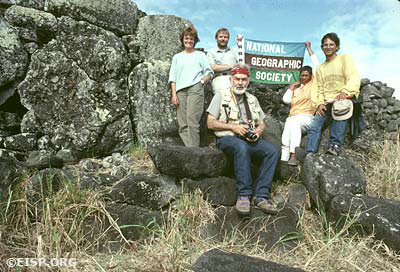

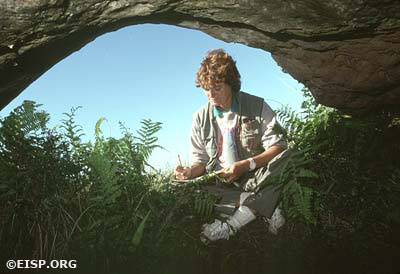

JVT sketching a cave containing a moai torso, Poike, Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Photo by David C. Ochsner, © JVT/EISP.

In addition to Anakena and the north coast, we worked many areas inland and on Poike. One of the most interesting inland ahu was Ahu O’Pepe—the original home of the basalt statue now in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution. The platform itself is simple and uncomplicated, and probably had gone through at least two construction phases. The style of the structure is similar to other inland sites. It lacks the architectural elaboration of the larger, more complex coastal platforms, and there are seven statues, all well within the average for those found on ahu.

JVT documenting the moai torso found in a cave, Poike, Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Photo by David C. Ochsner, © JVT/EISP.

In 1987 we had made a wonderful, unique discovery at Ahu O’Pepe: a large statue fragment lying on the ahu platform bearing an incredible bas-relief carved komari (vulva). The komari is a ubiquitous design in the island’s rock art and wood sculpture, but no carving even remotely like the one at Ahu O’Pepe had been documented before, and none has been found since. We carried-on with documenting the statues and the site, mapped interesting features such as ten umu pae (stone hearths), made more detailed drawings, and searched for further clues. Putting the archaeological data together with the ethnographic data, we learned a lot about the importance of the site in the recent past.

A Rapa Nui family of the Tupahotu Rikiriki lineage claims the site today. According to knowledgeable elders, it might have been named after Ko Pepe, the man who, it is said, commissioned the ahu. The komari was very likely related in some way to similar designs used in initiation rituals and associated with the ceremonial site of Orongo. Within what Katherine Routledge called “living memory,” large family-based rituals were held at Ahu O’Pepe, and an aspect of them may have been female initiation.

Findings

Standing statue (88), exterior slope of Rano Raraku, Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Photo by David C. Ochsner, © JVT/EISP.

Data collected during our 1989 fieldwork were ample enough to suggest that statue type will relate to ahu type to a measured degree. Cumulative evidence gathered by other investigators on restored or excavated ahu sites can be integrated into the statue study to analyze the relationship of statue sequence (based upon type, style, and material) to ahu phase.

Jo Anne Van Tilburg and Curtiss H. Johnson preparing the seaward wall at Vinapu. Photo by David C. Ochsner, © JVT/EISP.

We have drawn two important conclusions. The first is that local stone was occasionally used for statue carving even though it was either inferior in texture or more difficult to work. In the case of the trachite statues on Poike a great deal of energy was spent working the very hard and dense stone. This effort was balanced by the local availability of the material, suggesting that political access to Rano Raraku was not available. The same was true on the north coast where local, inferior red scoria was chosen (on one site) rather than importing statues of tuff from the distant quarries of Rano Raraku. The symbolic value of the color red in the choice of scoria was an important variable in its selection and use.

The second conclusion is that, with the data base now significantly expanded, it appears that statue type overlapped in time on some sites, and that more than one type was used on a given site at the same time. Some stylistic variables (such as the mouth) are now much better documented. Some experimentation with style may have been going on locally before change or elaboration was widely accepted.

Want to know more?

Routledge, K. 1919. The Mystery of Easter Island. London: Sifton, Praed & Co.

Van Tilburg, J. 1987a. “Symbolic Archaeology on Easter Island.”Archaeology (40) 2, 26-23.

Van Tilburg, J. and P. Vargas C. 1987b. “Transition and transformation of Easter Island Sculpture: Recent archaeological evidence.” Zagreb, Yugoslavia. Paper presented, 12th International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences.

Graciela Hucke Atan preparing tuna (kahi) at EISP campsite, Anakena, Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Photo by David C. Ochsner, © JVT/EISP.

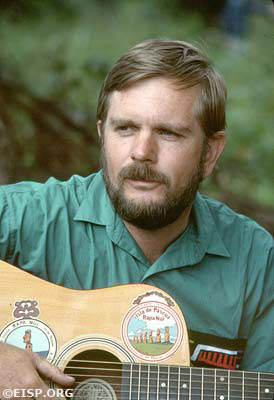

EISP team member Curtiss H. Johnson in camp, Anakena, Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Photo by David C. Ochsner, © JVT/EISP.

English

English  Español

Español