Easter Island Statue Project History: 2005-2006

GPS Mapping of Rano Raraku Quarry

EISP field crew, 2006: Henry Debey, Alice Hom, Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Cristián Arévalo Pakarati, Matthew Bates.

August 2006

Field Team

Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Ph.D. Project Director

Cristián Arévalo Pakarati, Project Co-director

Alice Hom, Database Manager

Matthew Bates, Project Surveyor

Henry Debey, Image Catalog Editor

Goals and Methods

Within Rano Raraku archaeological zone, the published maps (Cristino et al. 1981) indicate 680 localized “features” and 529 “sites.” Unlike the published survey quadrant maps, however, twenty-one types of map icons define the class of object localized. The definition and relationship of site and feature, the boundaries of a given site, and the inferred use, function, or purpose of a site or feature cluster is not clarified.

Our nomenclature drops the “site” and “feature” designation and re-defines them as surveyed “objects” located and mapped on the ground and capable of being considered as either sites or features, depending upon their individual circumstances. These objects, whether singly or in clusters, have been 1 of 6 flexible interpretive use or purpose descriptions (all widely acceptable in Easter Island studies).

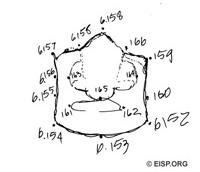

The EISP database has a survey identification code to denote 29 specific “object” types encountered in the field or in museum or archive collections. These object definition codes are clustered in 5 groups, with group 1 being Monumental Sculptural Objects (3-dimensional) and including moai and their frequently encountered, specific partial or complete forms.

Our field goals during this season were to complete collection of mapping points in the interior Section D; to collect mapping points on all “in transport” statues no matter where they are located, and to re-locate and document all previously mapped, non-sculptural objects in the eastern and exterior quarries.

In the Field

Relocation of previously mapped but un-documented objects in Rano Raraku exterior and eastern quarries was facilitated by the definitions of the objects provided by the map icons; unfortunately, however, modern disturbance of the ground surface area is extensive, and many objects could not be re-located. This was also true on the interior. Alignments and other previously mapped objects near the lakeshore (as it exists today) were often difficult or impossible to locate. The grass was so high and thick in one area that it took many hours to find “Little Tukuturi.” Mapped originally by Cristino et al 1981 and documented by Van Tilburg in 1984, it was lost to our mapping effort until Alice Hom finally found and cleared it.

Jo Anne Van Tilburg and Matthew Bates navigate the reeds of Rano Raraku crater to survey in the waterline, 2006. Photo: H. Debey

We differentiated 19 discrete quarries within Rano Raraku. Those in Section C (west) are defined by the presence and extent of variously sloped, exposed rock (papa). Those in Section D (east) are defined by lines drawn from natural fissures in the rock which are discernable as natural breaks or cracks in the rim edge. This geological differentiation was noted and described by Routledge (1919:177-8) and is reflected in the areas of Sections C and D as established by Cristino et al. 1981.

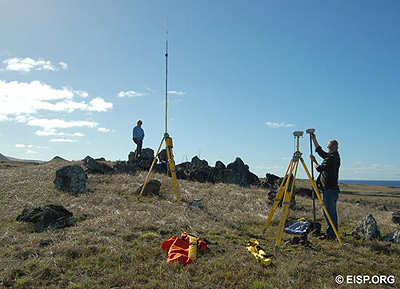

Jo Anne Van Tilburg and Matthew Bates set up to survey the statue transport road, 2006. Photo: H. Debey © JVT.

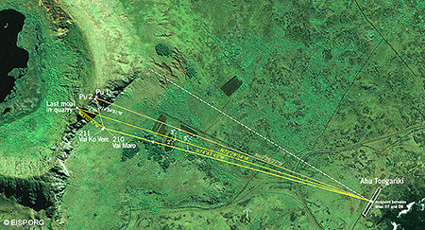

Points of all statues “in transport” in Rano Raraku zone were collected by Matthew Bates on sketches by Cristián Arévalo Pakarati. We moved our control station twice to collect points on all statues along what Routledge called the “southern image road.” Quarries were mapped, rock art located and coordinated with drawings by Henry Lavachery (1939), and statues were more fully delineated in the eastern quarries. Two statues vividly described by Routledge (1919: 193) were investigated. The statues had, it was said “marked a boundary; the line of demarcation led between them, from the fissure in the cliff above right down to the middle statue in the great Tongariki terrace.”

We tested the ethnographic “boundary marker” data provided to her by unnamed Rapanui consultants (one of whom was very probably “Langitopa”) and found it not credible as given. While a line of sight between the statues and Ahu Tongariki does exist, it is not a direct line to the mid-point of the ahu as presently restored. More interesting, actually, is our observation that the “direct line” is substantially to the east and marks the terminus of Rano Raraku.

Findings

Our mapping project has allowed us to verify without doubt that Rano Raraku was what archaeologist’s call “a terminal source of production” in which the final product (the moai) was produced and then conveyed to the island. Secondly, it was also a local zone of production in which the final product was retained or conveyed to the eastern region at roughly double the rate it was conveyed to the western region.

Given the lack of variability in evident quarrying techniques, it is not surprising that shapes and sizes of moai are essentially standardized. The control of technique and product reveals a relatively high level of skilled craftsmanship.

The frequency of mistakes in statue production is extremely small. The number of discarded or rejected statues is also small, and usually the result of faults in the stone material rather than mistakes of the human hand.

When the number of these discarded or rejected statues is compared to the total quantity of statues produced, we see that manufacturing techniques were fairly sophisticated. Methods for correcting errors, including re-carving of such features as the hands, are evident.

There is no evidence that access to the quarry material itself was restricted. However, a ring of hare paenga foundations delineating high-status structures was mapped by Cristino et al. 1981 as encircling the exterior periphery of the volcano. This suggests some sort of restricted access. Furthermore, the entrance to the (west) quarries in Section C is marked at the toe of the slope by a paenga; on the opposite (east) side of the crater in Section D the exit is marked similarly by another paenga.

Stone resource procurement in the interior quarries was highly directed towards the type and accessibility of the outcrops. The general picture that is emerging is that quarrying was systematic and undertaken for short periods or at irregular intervals.

Finally, it is completely evident in the distribution, total numbers, size, and weight of all documented sculptural objects (moai, heads, torsos, fragments) that parity and balance in these between east/west districts of the island as a whole were hallmarks of sculptural tradition. This appears to have been the result of managed production strategies closely tied to surplus food production.

Related Publications

Van Tilburg, J. and C. Arévalo P. “Archaeology and Ancient Aesthetics: Mapping the Sculptural Imagination of Rapa Nui.” Paper delivered and in press, Gotland University Conference, 2007.

Van Tilburg, J. C. Arévalo P., A. Hom. “GPS Mapping, Archaeological Database Management and the Conservation of Easter Island Statues”Documentation Strategy Handbook.Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

English

English  Español

Español