Statues and Rock Art: Rano Raraku and Rano Kau

Like Rano Raraku, Rano Kau, in the western, higher ranked district of [Ko] Tu’u also contains a freshwater lake 1 km in diameter. In sharp contrast, however, Rano Kau is formed not of tuff but of locally quarried dark gray to black basalt and related types of smooth, dense and hard volcanic rocks.

Rano Raraku and Rano Kau were each believed to embody aspects of Rapanui identity, history, and mythological narrative. Each was uniquely exploited for the main purpose of expressing the shared cultural awareness of deeply ingrained and ancient status alignments. Alternative forms of the carvers’ art (sculpture in Rano Raraku and petroglyphs at Rano Kau) stated and reinforced the main social east/west division through form, style, iconography, and metaphor.

Rano Raraku and Rano Kau, while dissimilar in terms of available stone resources, were alike in terms of visually evident morphology, landscape dominance, cultural exploitation, and purpose of place.

Orongo emerged as a ceremonial site in cultural and political counterpoint to the socio-economic challenge of Hotu Iti. The expansion of the Hotu Iti district from about c. A.D. 1280 is based upon agricultural success and culminates in the construction of Ahu Tongarikic. A.D. 1500.

The east/west division we discern within Rano Raraku reflects the ancient and pragmatic recognition of geological reality in terms of the distribution of the resource and the incorporation of that reality into the division of space based upon regional status history.

Controlling and managing the inevitable emergence of individual and group competition was crucial to the basic political goal of the Rapanui ruling class: successful retention of the paramount chief title. With time, however, and in the small-scale, marginal island environment of Rapa Nui, chiefly privilege—and the objects and iconography that legitimated it—became increasingly open to challenge.

According to Rapanui genealogy, there were ten “tribes” (mata) that descended from the sons and grandsons of Hotu Matu`a.1 The highest ranked mata was the Miru, who through the Honga lineage held exclusive title to the hereditary office of paramount chief (ariki mau).2 All Miru were aristocrats (ariki paka) who claimed a “real or fictitious relationship” to the king’s family, and commoners (hurumanu) held status through their lineage head’s rank.3 Métraux states that “there is no evidence in literature or in modern traditions that the ariki title was held by tribes other than the Miru.”4 The highest-ranked class of Rapanui priests (ivi atua) was also drawn, like the paramount chief, from the Miru. Thus the religious and political, sacred and secular offices were all centered in one dominating tribe.

Rapanui society appears to have been structured on an asymmetric political dualism. The east/west regions were distinct but connected to each other in an ancestral, status-based production and trade network. District-wide agricultural and marine resources were complementary in an ecologically balanced community until about A.D. 1250-80.

Our data contain 202 sites in the Ko Tu’u (west) district on which 334 sculptural objects (statues, heads, torsos) have been inventoried. In Hotu Iti (east) we have 237 sites on which 959 sculptural objects have been inventoried. The latter total is skewed by the presence of Rano Raraku in Hotu Iti and the count of exterior statues as within that district. Even if, however, the total number of statues still in Rano Raraku is removed from the equation, the east still produced and retained roughly double the number of statues.

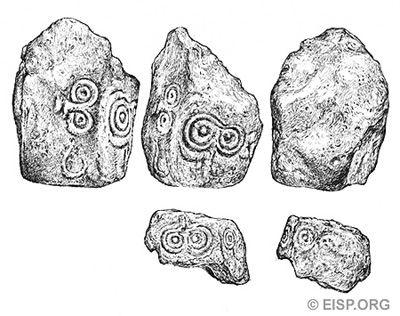

Detail of Makemake petroglyphs on basalt "pillar" drawn by Cristiàn Arèvalo Pakarati in 2006 © JVT/EISP.

In summary, there appears to have been generalized moai exchange over the entire island; an elite monopoly by the west district of moai iconography necessary to maintain social status; a subordinate challenge to traditional authority by the east district based upon successful agricultural intensification and acted out through increased moai size and numbers.

- Stevenson ( pers comm. 2002) reconstructs boundaries of 11 “clans” [↩]

- Some legends suggest that Hotu Matu`a’s first-born son, “Tuu-ma-heke,” returned to the original homeland, leaving the second son, Miru, from whom the dominant Honga lineage of the Miru ramage (mata) descends. [↩]

- Métraux 1940:129 [↩]

- Ibid [↩]

English

English  Español

Español