Field Dispatches: July 2003

Rano Raraku Interior Mapping Project Phase Six

Dear EISP colleagues and site visitors,

Iaorana korua! Welcome to EISP’s dispatches, jottings, and journal entries, sent to you by our 2003 field team on Rapa Nui. Notes, footnotes, and field notes…our records and reminders of work done, people encountered, questions posed, and ideas explored. We are happy to share with you our adventures on Rapa Nui.

—Jo Anne Van Tilburg and the EISP 2003 Field Team

8 July 2003: Departure from LAX

Always eager to depart for Rapa Nui, I am always reluctant to leave home and family. This is, by my imprecise count, at least the twentieth journey I have made to the island since my first in 1981. Even though I’m only one of many “northern shadows flitting across a southern landscape,” I still fancy myself an explorer. I love the adventure of each new field season and its promise of discovery!

Bill White, Alana Perlin and I are the first to depart LAX, and Peter Boniface will follow. EISP co-investigator Cristián Arévalo Pakarati will, as always, join us on our arrival on Rapa Nui. So, too, will Susana Nahoe Arellano, a new member of our team. Susana is a Licenciada in Anthropology (Universidad de Chile) with experience in Rapa Nui archaeology.

Bill White is a long-time volunteer at the UCLA Rock Art Archive, a professional photographer and film producer who worked with us during our November, 2002 field season in the inner quarries of Section D, Rano Raraku. He will act as videographer and surveyor’s assistant, but is also compiling a documentary about EISP history.

Alana Perlin is one of the Archive’s talented design students, all recruited by Gordon Hull and trained in EISP goals and methods by Alice Hom, our data manager. This is Alana’s first trip to Easter Island. She is carrying two digital cameras (one with a calibrated lens) and a laptop with the complete EISP image database, the total statue metric database, research records, and field notes.

Dr. Peter Boniface, of Cal Poly Pomona, is project surveyor. In July 2002 he initiated our survey in the inner quarries of Rano Raraku at Section C. Peter will bring with him three Ashtec satellite receivers, two GPS units, and a laser theodolite…thousands of dollars worth of wondrous mapping technology that will allow us to pinpoint statue positions within a centimeter level of accuracy. He plans to use the laser theodolite and calibrated lens camera to collect photogrammetric data on one of the statues standing on the interior quarry slope.

As for me, I will do my best to keep us all on track, motivated, and moving forward toward our final goal of surveying, mapping, and imaging the statues in the interior of Rano Raraku. In this I have the benefit of a strong support system in the island community, talented team members and, most importantly, a long-standing collaboration with Cristián.

Alice has created a spreadsheet showing the work we have accomplished to date. I have prioritized the information we still need to collect and defined a series of data queries….all distilled from intensive analysis of what we learned in our July and November 2002 field seasons.

My main field task is to measure and describe all of the statues we have found in the quarries, clarify their contexts and stages of carving, and compare their design attributes with our existing records. I have brought along a photocopied set of the sketchy excavation notes Katherine Routledge made during her Mana Expedition to Easter Island in 1914, and hope to pinpoint the statues she excavated. If we can do that successfully we will have nearly 90 years of priceless observation data in our files!

We are carrying the tools we need to get the job done: cameras, tripods, booms, film, compasses, calculators, and miles of duct tape. We also have stacks of field forms for collecting statue measurements and conservation observations, and for recording image records. File keeping is not the most glamorous part of archaeology, of course, but it is essential.

Each of us, I suspect, has also packed our own fertile imagination…travelers’ dreams of the mysteries and discoveries lying ahead on Easter Island.

—Cheers! Jo Anne Van Tilburg

12 July 2003: In Katherine’s Footsteps

Cristián and I decided that today was a good day to walk what Katherine Routledge called the “northern image road.” We haven’t done that since 1990, and we want to remind ourselves of the statues (moai) lying along the road from Rano Raraku toward La Pérouse. If these statues come from the crater’s interior we might be able to match them with their respective quarries. I love being along this road…it’s an ancient path through rock cobbled, deep grass into the quiet heart of the island.

The statues, sadly, are more deteriorated than our records show them to have been in 1990. We use a GPS to record features related to the statues, includingumu pae (cooking places), stone alignments, and a small ahu (ceremonial platform) of modest size with two statue torsos. Alana and Bill add images to our record; we picnic at a favorite spot and end a productive, fascinating day with one of Rapa Nui’s matchless sunsets.

—Jo Anne Van Tilburg

16 July 2003: Peter’s Arrival, First Field Day

Peter arrived Sunday evening (July 13), and after a day of relaxation (joining us on a wave-splashed boat trip around Poike) we embarked upon our first field day in the interior of Rano Raraku. We searched out the survey control points we had established in July 2002, and then staked out Area D. Half a dozen white and red survey rods now mark the dauntingly large expanse of the quarries we will begin mapping tomorrow. Gulp.

—Jo Anne Van Tilburg

16 July 2003: A Note From Bill

The enormous statues and the exotic people of Easter Island have fascinated me since I first heard of them as a boy growing up in Minnesota.

I now live in Los Angeles where I am a film producer and photographer. I am also very passionate about archaeology and anthropology and will soon complete the requirements for a Certificate in Archaeology at UCLA.

My studies at UCLA have included working with Dr. Jo Anne Van Tilburg at the Rock Art Archive, documenting rock art in several Southern California sites.

When Jo Anne asked me last year to join her and her team on Easter Island to photograph moai in the quarry I jumped at the chance. That expedition was marvelous and we accomplished a lot. Not only are the statues and the physical parts of the island intriguing, the people of Rapa Nui are fascinating and very hospitable.

The moai are everything I imagined and more: enormous, imposing, awe-inspiring, mysterious, unforgettable.

—Bill White

18 July 2003: Umu Tahu

Today my long-time friend Graciela Hucke and her husband Alfonso Rapu, along with our crew and Rapa Nui friends, celebrated the beginning of field work with a traditional umu tahu. The requisite white chicken was killed and cooked, the poi was mouthwatering, and Graciela’s kind words of blessing, friendship, and good luck launched our field season with cheering warmth.

—Jo Anne Van Tilburg

19 July 2003: A Day in the Field

Susana joined us today, and everyone fell instantly in love with her cheerful enthusiasm and willing energy. Together the six of us pull our equipment out of the back of Cristián’s truck, load up and slog uphill through a deep gap that forms the entrance to the interior of Rano Raraku quarry. We pass a statue, stuck in the gap on its long-ago journey out of the quarry. Katherine Routledge excavated the next statue we encounter, lying on the brink of its descent into the gap. Her notes say that she dug its entire right side “for signs of moving” but found nothing. She did, however, unearth a carving tool (toki) at 4’ 3” and sketched the statue’s finely carved ear detail.

Alana and Susana turn to and begin to clear the grass and document the statue as it is today…during the Routledge excavation the statue fell over to the side of its own weight. This is the first time they have worked together as a team, and in no time they find a cheerful and compatible rhythm in Spanish and English. The rest of us turn to wind our way downward into the crater and then along a pathway dotted with standing statues.

Susana working in the field. © EISP 2003.

The interior is thick with grass, and drifts of a bright green shrub called chocho engulf some of the statues. That damnable plant is an introduced nuisance that raises the already rather high humidity in the interior—to the statues’ obvious detriment —and is seemingly unstoppable. One of the major goals of the Chilean National Park Service (CONAF) is to eliminate it.

The lake that forms a deep, reflective eye at the heart of the quarry is still. The bright green reed called totora (Scripus sp) that fringes it was naturally introduced some 37,000 years ago. A small knot of tough island horses stands shoulder deep in lakeside muck, their russet and butterscotch coats slick with moisture.

We mapped the westernmost section (Area C) in July and November of 2002, so now we head eastward in a wide arc toward Area D. We drop our gear and set ourselves up in a sheltering quarry marked by a conspicuously large, white-painted message reading “Baquedano 1902.” Hawks whirl overhead, the sun’s slanting morning rays reveal the tool marks of ancient carvers on the quarry walls, and our day in the field begins.

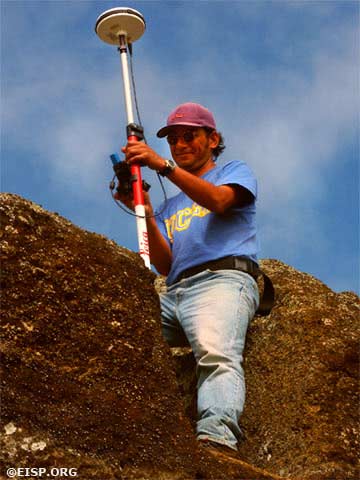

Peter sets up the base GPS survey station on the path at the east end of the quarry. The bright orange tripod is armed with two satellite receivers that look like miniature flying saucers, and within seconds they are humming along in silent concert with eight overhead satellites. How odd…this isolated little island is under the gaze of so many electronic eyes!

Bill is our “rodman.” His job is to climb the sloping papa (exposed tuff panels) with the GPS rover mounted on a survey rod. Placing the tip of the rod on the rock surface or next to a statue at the precise point Cristián, our cartographer, directs him to, Bill levels it and then marks the spot with the GPS rover. Cristián records the survey point on his map, and then they move on. It is a precise and repetitive task enriched by magnificent views and punctuated by heart-stopping balancing acts on crumbling cliffs.

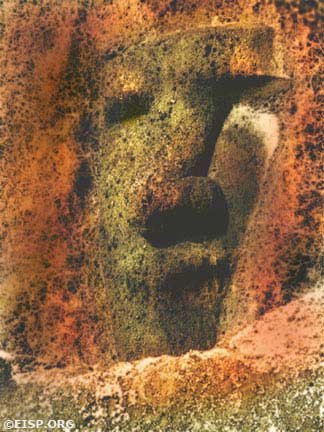

Some of the statues are blocked out and others are undercut, but many are mere shadows in the eroded rock, and it takes a practiced eye to find them. Others are overrun with grass, covered with grass seed, or sprayed with lichens. Sometimes grass grows right out of their crumbled stone surfaces and, as Susana says, it is “eating the moai.”

I am recording a series of observations about stone surface condition and other conservation factors. I began collecting these data on statues outside of the quarry in 1989, and they now constitute a valuable record of statue erosion and other changes over time. The statues in the interior quarries of Rano Raraku are often carved of inferior stone, and pulverization or delamination of the surface is common.

Lt. David R. Ritchie of the Mana Expedition established the base contour map for Rano Raraku. Universidad de Chile researchers Patricia Vargas C., Claudio Cristino F. and their team took 4 gross measurements of many statues, and refined a list of measurements necessary for project surveyor Roberto Izaurieta S. to illustrate statues in exterior quarries A and B. I based the first field season of EISP on this pioneering work, but in 1983 innovated the very precise method of statue documentation we have since followed.

The Universidad de Chile localized standing statues on slopes in the interior and exterior with identification numbers. They established parameters of interior quarries C and D but did not survey them, keyed in many related archaeological features, and published three fine maps of Rano Raraku in 1981.

We will use their maps as a guide to the interior slopes, and will incorporate their numbering system into our own as reference, but in the final analysis will create a completely new contour and feature map. Our survey will extend the parameters of Sections C and D, localize every statue and shaped block in the process of becoming a statue, map them in place and add them to the EISP database. The technology available today allows for great precision and reliability.

Fourteen stages of carving were defined in the exterior quarries, but here in the interior quarries we are faced with a rather different picture. One of our tasks is to refine the description of carving stages, and to try to gain insight into how the carvers and other experts worked here. We have our work cut out for us, but we’re all ready to go!

—Jo Anne Van Tilburg

20 July 2003: Footnotes: Progress Report

It’s a misty Sunday, and we take the day to catch up with the week. Peter says that all of our survey points have been successfully entered into the CAD program and burned to CD. Alana reports that we have 1,000 high resolution images successfully edited, renamed, and stored in our image database. Cristián’s map is gaining painstaking detail and I have edited my field notes and measurements for all of Section C and for 3 quarries in Section D. Whew!

We’ve taken breaks to boat around the massive coastline of Rano Kau and beyond the eroded cliffs of Poike. We’ve been lifted to dizzying heights out over the exterior slope of Rano Raraku in a cherry picker (thanks to the kindness of Rafael Rapu) for some once-in-a-lifetime pictures, hiked the north image road and along the northwest coast, picnicked in view of tumbling breakers and in the shelter of our “Baquedano 1902” home, and renewed our acquaintance with Rapa Nui people and statues. Life in the field is good!

—Jo Anne Van Tilburg

Bill White films the view from the cherry picker as other members of the field crew take it all in. © EISP 2003.

23 July 2003: A Note to Fellow Travelers

Dear Tourists:

Rano Raraku, in addition to being a natural wonder and a human-made marvel, is a sacred site. It holds within its embrace a cluster of figures in human form that represented, so far as we know, the “living faces” of Rapa Nui ancestors. Caring for this site, and for the patrimony of the island, is every visitor’s obligation. We have had the pleasure of meeting and talking with so many of you during these past few days, and it is clear that you are all impressed and, in some cases, awestruck by what you see. In that spirit, please pay attention to where you are walking…watch your step. Beneath your feet may lay the recumbent figure of a moai.

Sincerely, EISP

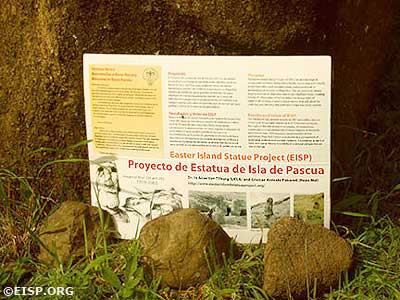

An informational park service sign about EISP and the importance of preserving the moai. © EISP 2003.

At the request of CONAF and the Consejo de Monumentos, we placed a sign that describes our project to tourists who traverse the interior quarry path. We have prepared a small brochure that gives details on our work, and pass it out to inquisitive visitors who stop to chat. Everyone we have met is deeply concerned and respectful of Rano Raraku, but they also need clear guidelines as to what is expected of them. Susana, who heads the island’s official Sernatur tourist office, doesn’t hesitate to direct visitors along the right paths, and they seem to appreciate it. We hope our work, in addition to pointing out conservation priorities, will help inform future decisions regarding tourist traffic in Rano Raraku.

—Jo Anne Van Tilburg

Monday 28 July 2003: Some Friendly Greetings…

Hello from Easter Island!

My job on the EISP project is to use GPS (Global Positioning System) to produce a map of the quarries from which the statues were carved. For the past two weeks we have been working in Rano Raraku crater, mapping the detail, point by point. The GPS receivers were kindly loaned to the project by Thales Navigation (France) and have performed flawlessly, giving us latitude, longitude, and elevation for each point to an accuracy of about half an inch. On Friday we used Photogrammetry to capture 30 images of a single statue. The images will be used by the Vexcel Corporation (Boulder CO.) to produce a geometrically precise 3D computer model of the statue. Today, with the rain pouring down, I will be converting the GPS points into a digital map using Microstation CADD, a computer-aided drawing program, and will be saying goodbye to our colleague Bill White who flies to LA this morning. Happy landings Bill!

—Peter Boniface

A lone moai suddenly appeared on a rock-strewn hill during our first field day, silhouetted against a tree on the north image road. The solitary statue highlights the island’s unique character, where seemingly empty hills and fields hide magnificent works of art and remnants of ancient existence. Photographing the moai in the Rano Raraku volcano has brought the statues to life, where we have observed lateral moai in the initial stages of carving and towering faces refined into stylized form. The Easter Island Statue Project has been preserving the moai through many methods of documentation, and my role as the project’s photographer and graphic artist has enabled me to compile a new database rich with images and field notes. The Rapa Nui people’s friendliness (kissing is a part of greeting) and the landscape’s serenity have made the experience great, and the Hotel Otai’s accommodation of my vegan diet has been exceptional. Thanks to our team for all of the effort and the Rock Art Archive for supporting us.

—Alana Perlin

August 1, 2003: Rainy Days and Mondays

For the past few days our Rapa Nui friends have predicted rain. The reason we should expect it, they say, is that the moon is now “dark.” It is a time of changing winds. Fish hide in the offshore depths and unwary archaeologists get drenched!

Still, we slog into the quarry. The wet grass and chocho sparkle with raindrops whenever the sun peeks through pink and mauve clouds, and nearly every day we are treated to awesome rainbows. The papa is slippery and crumbly underfoot, and the survey work slows as everyone becomes more cautious. We watch the darkening sky and then duck and cover whenever Cristián shouts, “It’s coming!”

After Bill left for the States, we welcomed a new team member: Rapa Nui artist Cristián Silva Araki. In the real, non-field work world he is a flight attendant for LAN Chile. He’s a great addition to our team, and we have dubbed him Cristián Segundo. He is helping Cristián Primero with the sketch map and, under Peter’s direction, is taking over some of Bill’s survey duties. Cristián is a quick study. By the end of his first two days in the field he is entering survey points in the GPS rover while, at the same time, tottering on the edge of a narrow carving canal that snakes down over the face of Quarry D-1, the largest in the interior. The location of each survey point is marked precisely on our sketch map. On good days we take more than 300 points to move, centimeter by centimeter, through the canals and quarries.

The value of such precision to both archaeology and conservation is immediately obvious. Carving procedures, methods, tools, and stages of statue development are slowly revealed in minute detail. Mapping the proportion, width, shape, and slant of the canals in which the carvers stood, for example, allows us to calculate the potential size and deployment of the work force needed to complete each statue. We can reconstruct the progressive unfolding of work stages on the biggest statues.

A large moai in the quarry. © EISP 2003.

Alana Perlin in the field. © EISP 2003.

Alana is capturing micro images of tool marks, and in some of the 12 individual quarries we have mapped it is possible to discern whether a carver was right or left handed. She is also imaging design details of ears, hands, and other features, as well as the presence and patterns of lichens, mosses, and grasses on the surfaces of statues. One result of our work this season will be a CD-ROM for the Chilean National Park that describes environmental challenges to statue integrity.

Moai 111 in Quarry D-7. © EISP 2003.

Writing in 1919, Katherine Routledge, co-leader (with her husband) of the Mana Expedition to Easter Island, speculated that Moai 111 in Quarry D-7 was carved “contrary to all usual methods, and it seems improbable that it was intended to make it into a standing statue.” Our map suggests that the carvers were intending to remove it. While transporting statues across the Rapa Nui landscape was certainly an achievement of method and manpower, I have come to believe that removing and manipulating them in the quarries was an even greater challenge.

—Jo Anne Van Tilburg

3 August 2003

We are down to the wire now, and even though it’s raining and we should be enjoying our Sunday leisure, we have decided to go into the field for a last big push. We have to finish some neglected details of three papa in Section C and capture the last points in Quarry D-1, a complex maze of canals and statues. Cristián (Segundo) has to fly tonight, so we have to move fast…we do, and end this field season with a great barbeque feast and some (a lot!) of Chile’s fine wines.

—Jo Anne Van Tilburg

Rock art in the form of a make-make at Baquedano. © EISP 2003.

6 August 2003: Maururu!

We have a few days to relax and reflect before our departure from the clear light and rainy sounds of the island. Of widely different backgrounds, natures, and interests, we have come together to share good work, fun, personal viewpoints, intellectual interests, and profound challenges. From afar, the whine of a jet approaches on the horizon—maururu, thank you, gracias.

—Jo Anne Van Tilburg

The Easter Island Statue Project comprises many layers of information, from drawings and photographs to measurements and a GPS survey of Rano Raraku’s interior quarries. The powerful EISP database preserves the moai through the passage of time, and provides an unprecedented basis for analysis. The July–August 2003 dispatches from the field have come to a close, so enjoy the photos and even an original artwork inspired by the moai.

—Alana Perlin

Original artwork inspired by the moai of Rapa Nui. © EISP 2003.

English

English  Español

Español