Writing Routledge: Her Field Notes and Their Value to Science

This is an edited excerpt from a presentation entitled “Sex, Lies and Fieldnotes: A Skeptic on Easter Island” given at The Skeptic Society, Cal Tech, Pasadena, 2003

Katherine Routledge was the first woman archaeologist to work in Polynesia. Attracted by the international mystery of Easter Island’s giant stone statues, she and her husband William Scoresby Routledge built their own yacht. They christened her Mana, a Polynesian word meaning spiritual power and, on Feb. 28, 1913, set sail from Southampton, England. Over a year later, the Mana Expedition arrived on storied Easter Island (called Rapa Nui).

Over the next 17 months Katherine Routledge mapped and measured her way through hundreds of prehistoric sites. With Scoresby away on a dangerous and near-fatal wartime journey to mainland Chile, Katherine was alone on Easter Island for an unexpectedly long 3 months and 10 days. Deliberately, she turned her attention from statues to people, from archaeology to ethnography, probing what she so aptly called “living memory.”

Her partner in this effort was a charismatic Easter Islander named Juan Tepano. Their work together resulted in a mass of fieldnotes, journals, genealogies, photographs and maps, and laid the groundwork for the recovery of Easter Island culture history. She sorted out, or tried to, the “tendency to glide” around the truth that some of her oldest consultants displayed (and whom Tepano frankly called “liars”). As the only woman on the expedition, she contended with islander gossip about the long hours she spent with Tepano in the field. After her return to England, she was patronized and marginalized by some male colleagues.

In 1919, much of the expedition’s valuable information appeared in a successful book Routledge wrote for the general reader called The Mystery of Easter Island: The Story of an Expedition. The book was generally well received, and a second edition was published within a year. Considered by a few to be a somewhat typical Englishwoman’s book of travel experiences, others saw it as the valuable ethnography it was, and eagerly awaited the “more scientific” book she promised would follow. Her second book was never written and, for the next 50 years, her fieldnotes were thought to have been lost or destroyed.

By 1928 Katherine had become desperately ill. She and Scoresby parted dramatically during an acrimonious and public dispute involving their finances and her fieldnotes. Katherine chucked all of her husband’s clothes out the second story window of her Hyde Park home, shut herself up and refused to see anyone. She waged a desperate battle in the media that resulted in a court order sequestering her property and funds. Toward the end of the summer of 1928, Katherine Routledge was actually kidnapped from her fortified home. Scoresby and the others forced her into a waiting ambulance and drove her to a distant asylum. One year later, Scoresby deposited the bulk of Katherine’s fieldnotes, correspondence, Mana logbooks and accounts on loan with the Royal Geographical Society in London.

After Katherine died in 1935, Scoresby made no effort to publish a report based on her fieldnotes. In 1948, nine years after Scoresby’s death, the Royal Geographical Society’s Picture Collection acquired 142 photographic negatives from John Charles Dundas Harington, one of Scoresby’s heirs and son of his best friend, Sir Richard Harington.

From the 1930s to the 1950s, Mana Expedition papers at the Royal Geographical Society, together with glass lantern slides Scoresby donated to the British Museum in 1925, constituted the largest collection of original Easter Island field data available for research anywhere in the world. Scoresby replied to inquiries that Mana Expedition fieldnotes were all lost “in consequence of my wife’s mental illness.” Eventually, it came to be accepted wisdom that no fieldnotes existed.

In 1935, the year Katherine died, Scoresby relocated to Kyrenia, Cyprus. A teenager named Eve Dray met Scoresby aboard the ship she and her father, Thomas Dray, were taking from England to Cyprus. Scoresby became friends with Thomas Dray and built a permanent residence on Cyprus. When Scoresby died in 1939, Dray inherited the property and remained there until his death in 1960.

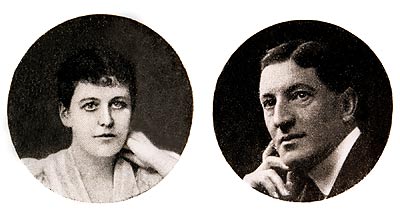

Eve Dray Stewart, who rescued Mana Expedition papers long lost, and her archaeologist husband James Stewart, 1960. (Photo courtesy Eve Dray Stewart.)

In 1961, Eve Dray, now married to archaeologist James Stewart, was living temporarily in Thomas Dray’s Cyprus house while Stewart was supervising a dig of two Bronze Age cemeteries near Karmi. In the evenings, Eve idly began to look through her deceased father’s belongings. Pulling papers out of a cupboard under a large bookcase, she discovered an eccentric hoard of Scoresby Routledge’s photos and personal memorabilia.

Eve found priceless original field survey maps and finished maps of Easter Island drafted by the Mana Expedition’s surveyor Lt. D.R. Ritchie, vocabulary cards and genealogical records made by Katherine on the island of Mangareva. Having no interest in Easter Island but recognizing immediately the value to science of what she had found, Eve turned the papers over to Stewart’s departmental secretary, Mrs. Betty Cameron, who forwarded them to the Royal Geographical Society.

With this new addition, the Society’s archives contained a treasure trove of Routledge Easter Island information. While everything was plainly referenced in the archives list, Easter Island researchers were apparently not aware of their existence. Even Thor Heyerdahl, who was a Fellow of the Society, failed to consult them. From 1960 to 1981, reports that came to be regarded as primers for archaeologists, anthropologists and linguists were published. None of them had the benefit of Katherine Routledge’s fieldnotes.

In 1982, during my first field season on Rapa Nui, my husband hand-carried to Easter Island a microfilm reader that was purchased with funds from the UCLA Friends of Archaeology. Routledge’s notes had been “discovered” in the Royal Geographical Society archives (although their history was still garbled). Microfilm copies were made available to a number of research institutions, and the microfilm reader was given to Chilean researchers then based on Easter Island.

Statue of Joseph Pease, Katherine Routledge’s paternal grandfather and Quaker “father of English railways,” Darlington, Northern England. (©1995 EISP/JVT/Photo: J. Van Tilburg)

I did not read Katherine’s fieldnotes at that time, but those who did said they were a disordered and nearly indecipherable, eclectic assortment of daily journal entries, site descriptions, genealogies, measurements of statues and interviews with informants. Copies of letters, published and unpublished newspaper articles and drafts of The Mystery of Easter Island were jumbled together with grocery lists and equipment vouchers. They remained essentially unread and rarely cited for a decade.

Not willing to rely on microfilm, especially when Routledge’s handwriting was difficult or impossible to read, I traveled to London to consult her original fieldnotes for the first time in 1985 and then at least once a year until 1994. In the beginning, my interest was purely scientific. I needed Katherine’s documentation to amplify my own field observations.

As I worked with her papers, however, I gradually became aware of her personality. I learned to clarify which of Katherine’s observations was first-hand and which came from her chief informant and close collaborator Juan Tepano. I came to understand some of the ways in which her field party interacted with the Easter Island people and with each other, and how those interactions had a seriously negative impact on the ability of members of the Mana Expedition to do their work.

Over time, my interest in Katherine Routledge grew as my knowledge of Easter Island became more intimate and better informed. I had never written a biography before I began work on Katherine’s story, but I grew up with a mother obsessed with her own English family’s history. Personal record keeping and genealogical investigations were major preoccupations of hers, so digging into someone else’s family records was not overly mysterious to me.

I expected to find the sorts of eccentric odds and ends that all fieldworkers save but, as I combed through Katherine Routledge’s papers, it slowly became obvious that they had been censored. My curiosity piqued, I dug deeper. Personal papers and photographs had clearly been removed and, in at least one case, destroyed. Someone had tried to obliterate the personality of Katherine from the stories embedded in her Easter Island fieldnotes. I wanted to know why.

Quaker Meeting House, attended by Katherine Routledge and her extended Pease family for generations, Darlington, England. (©1995 EISP/JVT/Photo: J. Van Tilburg)

Katherine Routledge’s Slone Square town house, one of many London residences she called home. (©1997 EISP/JVT/Photo: J. Van Tilburg)

Tracing Katherine’s story was surprisingly difficult at first. The path I took was shaded but then, at critical junctures, wonderful vistas opened or just the right guide fell into step beside me. I grew to feel that the work of researching Katherine’s life was, in odd and unlikely ways, guided by her desire to have her story told.

I began my quest in Darlington, County Durham, in the north of England, and journeyed there for the first time in August, 1996. The weather was fine and warm, the neat patchwork of fields a rich tapestry of yellow and green. I wondered if it had been the same when Katherine Routledge was born Katherine Maria Pease, daughter of one of Darlington’s wealthiest and most prominent Quaker families, in 1866.

Jo Anne Van Tilburg on the steps of Joseph Pease's “Southend,” now a modern hotel, Darlington Northern England. (©1995 EISP/JVT/Photo: J. Van Tilburg)

Eventually, I was drawn back to Darlington three times at different seasons of the year. I loved the springtime, when the lilacs were in bloom and the unruly beds of crocus flowers looked like spilled paint along the pathways. I stayed once at Southend, the estate of Katherine’s grandfather, family patriarch Joseph Pease, and sipped tea at Walworth Castle, her parents’ first real home. I visited the graves of her family, and attended meeting at the Quaker Meeting House in which she was brought up and married. I searched for stories of her in Darlington, and then realized with a terrible sense of loss that I had come too late.

From Darlington I tracked Katherine to her first home in London. Sheltering in the vestibule of a Sloane Square church one rainy day, I closed my umbrella, looked up and found myself looking directly at an obscure inscription that Katherine had once quoted in a long ago letter to Wilson Pease, her adored brother and confidant.

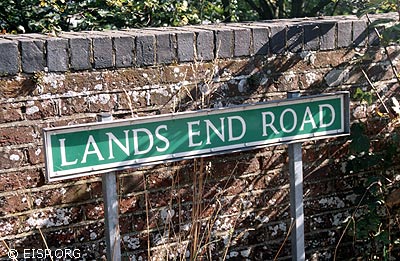

“Lands End” in Bursledon marks the location of the riverside honeymoon cottage where the Routledges spent their happiest years together. (©1997 EISP/JVT/Photo: J. Van Tilburg)

The romantic Hamble River cottage she shared with her husband was miraculously opened to me one day when the house’s current owner, a distant relative of Katherine’s, simply drove up, found me and my friend Reggie Barnes at his garden gate and invited us in. Precisely the same thing happened in front of her last home overlooking London’s Hyde Park. As my husband and I stood on the sidewalk, the owner walked out of the door and stopped to chat. Later, she toured us through the garden Katherine had loved and the home from which she had been so dramatically kidnapped.

On Easter Island, I pitched my tent on the same ground she chose for her own, and slept under the same stars. Once in 1983, I awoke in my rented house in Hanga Roa, Easter Island’s main village, to discover that a huge vessel carrying a cargo of logs had gone aground off the nearby coast. Islanders young and old were racing frantically about, making excited plans to recover the logs being dumped in an effort to float the foundered ship off the rocks. As I stood in the crowd on shore I was reminded of Katherine Routledge’s first night on Easter Island. She was in the Mataveri home of Henry Percy Edmunds, resident manager of the commercial firm leasing Easter Island for raising sheep. At his lamp-lit table after dinner, in a hushed voice and with his eyes half-closed, Edmunds told Katherine a story.

In June, 1913 El Dorado, a schooner carrying a deck load of timber and trading between Oregon and Chile, was caught in a gale and sank 700 miles off treeless Easter Island. Captain Benson, an American, and ten of his crew set out in a small, open boat. After nine days of hardship and near death, they sighted Easter Island. Scrambling up steep cliffs at the uninhabited eastern end of the island, they collapsed and then nearly died of thirst. Finally discovered and rescued, some of the crewmen settled on the island, but Captain Benson and the remainder sailed to Mangareva and then Tahiti in the same open boat. Percy Edmunds dispassionately hoped that, the next time a ship went down with a cargo of much-needed wood aboard, “she will have at least the commonsense to do so near Easter Island.” On that distant morning in 1983, Edmunds’ wish came true before my eyes.

Weeks later, I was with some Rapa Nui friends as we rode on horseback along the flanks of a volcano called Mauga Terevaka. Below us we saw the cargo ship that had now, after many weeks, been mercilessly stripped of everything. She was being towed to sea by a salvage vessel, and we knew that the plan was to sink her somewhere beyond the empty horizon. As we watched in wind-blown silence, the doomed vessel sounded her horn in a brave little farewell. That sad, watery tableau and lonely, almost human sound brought to mind Katherine’s description of another, earlier and very dramatic sinking.

On New Year’s Eve, 1914, Katherine witnessed a German vessel sink Jean, a captured French yacht, within sight of where we then stood, seventy years later. She described how the “graceful little barque” was towed “in a last Judas embrace.” The German warship “swooped round in great circles like an evil bird of prey, and every time that she came broadside on she fired at her victim.” As Katherine and her friends watched spellbound, Jean disappeared, joining “the company of ghosts in the ocean Hades below.”

There is, I think, a certain insight that comes from such shared experiences, however separated in time, and from deep roots in place. The momentous trifles of individual lives join across time and space to create an spheres of existence. Wilson Pease, Katherine’s favorite brother, noted after reading his father’s journals that “blood is thicker than ink, and a relationship to historical characters must introduce an intimate touch to history.” I have tried to use my own life experiences, a long acquaintance with Easter Island and a professional relationship to Katherine as an historical character to give her biography an “intimate touch.” Biographies are about the masks we all wear, but they are also mirrors that we hold up to our own lives.

Katherine Routledge’s fieldnotes are, in many ways, a living character in her story. While they are sometimes as hard to decipher as Rapa Nui’s mysterious rongorongo, I have learned to see differences in Katherine’s handwriting style, and understand how those differences transmit and reflect her state of mind. It is clear that Katherine’s fieldnotes are only a “refraction” of Rapa Nui reality, seen through her personal prism of real experience and, sometimes, psychic distress. Understanding, interpreting and making use of her fieldnotes to advance Easter Island scholarship requires that we understand as much as we can about Katherine Routledge’s life. What prepared her to do what she did? What shaped her, for good or ill, before she encountered Easter Island and, in the opinions of some in her family, was changed forever?

A traditional source to answer these questions is personal or family papers. I sought out and salvaged important papers on file with Katherine’s family, and with her husband’s family and friends. I worked hard to piece together the garbled story of Eve Dray and the rescue of Katherine’s fieldnotes on Cyprus. Katherine’s life before and after Easter Island emerges only through the shadowy perceptions, family traditions and personal experiences recorded by a very few people. All of this data, however, is now salvaged through this biography. It joins Katherine’s field notes as a framework for her research.

My biography of Katherine Routledge is not a full critique of the field methods of the Mana Expedition to Easter Island. Neither is it an analysis of Katherine Routledge’s research conclusions. Its central focus is one woman, one island and one moment in time when both came together. The chemistry and metaphysic of that moment is Katherine Routledge’s story and, in a small way, the story of Easter Island as well. Using and understanding her fieldnotes requires that every researcher know the context in which they were written.

Anthropologist Simon Ottenberg, writing in R. Sanjek’s Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology, says that fieldnotes are written attempts to impose order on the external world of our research as well as on our personal lives in the field, to grow up through understanding the culture we are studying, to perceive the realities of the interests and motivations of those who interact with us in the field. Our own increasing maturation and understanding is reflected in the changing nature of the notes as the field research progresses.

Katherine Routledge’s life, work and spiritual journey are distant from us in time. Yet her quest for self-discovery is a timely tale. It resonates with themes common to the stories of many women over many generations, and gives unity to the larger human story. Katherine understood the connections of people with places, of stories with history, and so did the Easter Island storytellers from whom she learned so much. The conjoining of her life with theirs came at the most opportune moment for both. Easter Island gave Katherine the peace she sought, but it also changed her life. Katherine Routledge gave the Easter Island people the gift of her intellect, allowing them to preserve, for all time, a version of their history that, without her, would have been lost to their descendants, to scholarship and to the outside world forever.

Want to know more?

Jo Anne Van Tilburg. Among Stone Giants: The Life of Katherine Routledge and her Remarkable Voyage to Easter Island. New York: Scribner’s 2003

External Links

Japan Times artice: Women to the fore in study of statues

Skeptic Society (Lecture available on VHS/Cassette/DVD)

English

English  Español

Español