Easter Island Statue Project History: 1982

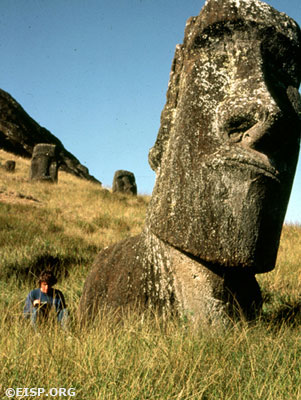

“There is still much to be done before all of the questions attendant on the statues of Easter Island can be answered. Little can be accomplished by theoretical approaches to the solution of the problem. What is now needed is a comprehensive and systematic field study and recording of the statues, followed by extensive excavations both in Rano Raraku and in other parts of the island.”

Arne Skjølsvold

Goals and Methods

The field goal of EISP is to accomplish 100% documentation of every moai on the island and in museum collections. The initial research goal was to collect enough data to create a formal and stylistic typology that, it was hoped, would be a significant aid in chronological studies. The first field season of EISP was in 1982. The first basic survey document was the Atlas Arqueológico de Isla de Pascua. The second was a list of 55 statue attributes isolated by Chilean archaeologists Cristinio F. and P. Vargas C. of the Centro de Estudios.

This was pre-digital fieldwork, of course, and precision and accuracy were big concerns. The first step was to create two recording forms. The first form was a two-page format for use in the field. On this, diagrams were drawn which clearly indicated where the measurements were to be taken. Dimensions were arranged on the diagrams in convenient groupings, and all measurements were taken at a given point or general area of the statue before moving on. Since I was working alone most of the time, the chief concern was to facilitate the work in an orderly fashion, as well as to minimize contact and avoid possible damage to the friable surface of the stone.

Having arrived at a workable field recording technique, the six-week field project began with reviewing Patrick McCoy’s unpublished field notes for quadrants 2,4,5, and 6, on file with the Centro de Estudios.

In the Field

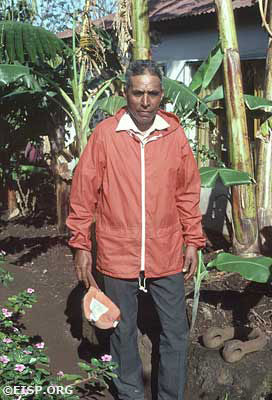

This first EISP season was conducted with nothing more than a compass, tape measure, camera, notebook, and statue measurement recording forms. Felipe Teao A., the Centro de Estudios’ regular guide and consultant, was absolutely indispensable in the field. On some of the more complex sites with big statues Gregg Sablic and his adopted Rapa Nui son, Stephen (Tuti) Pakarati, joined us. For a portion of the time architect Johnnes Van Tilburg assisted with structural details on coastal sites. In the end—in spite of some really terrible weather—we recorded 150 statues or fragments of statues at forty-eight sites in nine quadrangles.

Findings

Survey site numbers and a unique project number were required to identify all statues, and measurements were reported in a series of tables. A format for identifying non-survey sites was established. All previously recorded sites or statues were given appropriate cross-references when possible, and symbols were used to clarify why data were missing.Many statues were suffering various forms of environmental damage. We developed a checklist of conservation observations on such vital issues as stone surface condition relative to stone type, statue placement and position. These considerations would be addressed in the 1983 field season. The vast amount of data collected in six short weeks was impressive to the point of being overwhelming, but it was also manageable and potentially very enlightening.

Considering our information within the context of the site descriptions produced by McCoy, the survey as conducted to that date, and the political map as produced by the Mana Expedition to Easter Island in 1914-15, we concluded that the statues we recorded were within such tribal areas as the Haumoana, Marama, Ngatimo, and Ngaure. We further concluded that an analysis of stylistic attribute differences of moai within these political divisions had great potential if considered within the context of area patterns, tribal distribution, and architectural characteristics of ahu.

Want to Know More?

Van Tilburg, J. 1982. Easter Island statue project (El proyecto de estatuaria de Isla de Pascua). Vols. I (79 pp) and II (186 pp, 15 tables, 12 figures, 2 plans and 4 appendices, including UCLA and UC field recording forms and attribute lists). Copies on file, UCLA Rock Art Archive and Centro de Estudios Isla de Pascua.

English

English  Español

Español